The Lobster Theory is Greg Fishman’s latest book, using eighteen of his greatest analogies to describe different elements of jazz music theory. The illustrations are done by notable artist Mick Stevens, who has been an illustrator for the New Yorker for over thirty years.

As Greg Fishman says,

Many of the analogies are lighthearted and humorous, making them very user-friendly and easy to remember. The book is designed so that the chapters stand alone. You can read it cover-to-cover, or just go directly to any chapter that appeals to you.

Throughout the book, the imaginative illustrations by Mick Stevens convey the pure essence of my analogies. This unique combination of cartoons and analogies presents advanced musical concepts in an accessible way that everyone can enjoy.

I can personally attest to the uniqueness in his analogies and musical writings. The very first chapter, focusing on practicing, is probably the analogy I can relate to most of all.

Practicing And Lifting Weights

About two years ago, I went on a backpacking trip with some friends of mine in the Smokey Mountains. Of course, I’d been camping, even backpacking before. I am an Eagle Scout, after all! Long story short, after hiking miles each day, (it was a three day trip) all uphill, in the freezing cold, my body was pretty wrecked. This was my fitness crucible, and since then, I have been on a quest to become physically fit.

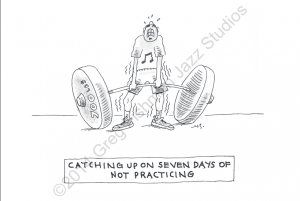

One of my friends from the trip is a Marine officer, and he invited me to come and train with him. He trained with a combination of heavy weight training, CrossFit style WOD’s (Workout Of the Day), and Olympic Lifts. I started lifting with him three times a week. He started me with some primary barbell training using basic techniques, and going up in weight each time. Quickly, I could feel and see myself getting stronger, it was great! Then school started again, but that was fine, because I was still going two or three times a week. Well, now tests were coming up, or a project, or whatever, and I’d take time from the gym to devote to that. When I finally went back, I tried to squat or deadlift what I previously lifted, and I’d fail! I couldn’t do it anymore. My muscles were weaker, I struggled to complete lifts with the right form, and I feared that I would hurt myself. I had to work my way back up to the weight.

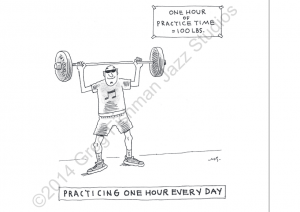

Greg’s analogy for practicing is almost the same as my personal story. When you practice everyday, even for a short amount of time, you will improve. Due to the way the human brain works and processes information, practicing for an hour on Monday and an hour on Tuesday is much better than not practicing on Monday and practicing for two hours on Tuesday. Once you miss a day, you can’t really “make up” for lost time in the same way.

Unfortunately, I can relate to this in the musical world as well as the lifting world. I am ashamed to say there have been many weeks in my schooling where I have presentation due, or a big project at work comes up, and my practicing gets shunted to the wayside. It’s the day before my lesson, I try and work super hard to learn the pieces I should have been working on, but it’s never enough. I get in my lesson, and my teacher says, “What happened?”

Now, as Greg says in his book, missing a day of practice here and there isn’t going to be the end of your musical world. However, you will play better, and enjoy your music more if you commit more time to practicing. Even if it is merely ten minutes a day, it will make a huge difference in your performance.

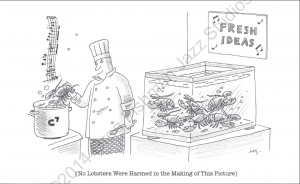

The Lobster Theory

Imagine you’re at a super swanky restaurant, you’ve gone the whole nine-yards, held back no expense. You order the lobster, because you love the buttery, delicious flavor of this clawed crustacean. The waiter brings it to you, and you partake, but… something just isn’t right. You ask the waiter, “Why does this fresh lobster taste funny?” He replies, “Oh, it’s not fresh, we use frozen lobster.” If you consider yourself to be a connoisseur of fine dining, you probably will not return to this establishment because you know that lobsters spoil almost immediately. To maintain freshness, the lobster must be cooked live, else it will taste stale.

In jazz, solos work in very much the same way. If you get to an “improvised solo” with all of your licks and lines planned before hand, you will lose the spontaneity, or “freshness” of the solo. Does this mean that Greg is suggesting in his book that you shouldn’t practice patterns, or scales or anything else of the like to avoid “dead lobsters” in your music? Certainly not! If you don’t expand you musical vocabulary, you won’t have any ideas to work with in the moment of your solo.

Whether you have a live or dead lobster doesn’t depend on the musical idea itself. Any idea could be live or dead. What makes it a “live” idea is the point in time when you think of it.

This is one of the truest forms of “improvisation” employed by not only jazz musicians, but actors and comedians as well.

These analogies, the second of which is also the title of the book, have far more information and ideas than I have presented here today. These are highly abridged versions infused with my interpretations and experiences.

To see the full analogies, grab your own copy of this fantastic and innovative new jazz book today! Just click on the link below to take you to the Jazzbooks website, where you can also watch a video by Greg Fishman explaining more about the Lobster Theory.

One reply on “The Lobster Theory”

The Lobster Theory is an excellent book. The presentation of Jazz Theory in a style like Fishman’s is long overdue. I’m using it along side David Bakers How to Play BeBop 1 and a few scraps of info on playing my new Tenor Guitar. (my main tool is fretless bass). Have a look at the preview above and get your copy NOW. It’s Great.

Park Furlong